I was fortunate enough to observe the stunning Harvest Moon the other night. It hung in the sky in a kind of chemical, powdery orange glow, rather ominously I thought, too close for comfort, a belligerent guest barging drunkenly from room to room having gatecrashed a party.

I stopped the car in the lane anyway in an attempt to take a photograph; I knew full well it was useless, as good as the iPhone is to capture anything in the daytime its paltry lens is no match for smudgy darkness. Maybe if it had been a silver, sulphurous full moon I’d have at least stood a better chance of acquiring the image.

Although the night sky wasn’t ideal for moon-gazing the orb pushed its unusual presence over the fields so that every living creature going about its nocturnal business surely must have at least paused for a second to look up. Was that a fox I could see, its yellow eyes laser-bright in their malevolent intensity? I’m sure he recognised I wished him no enmity, that clever and calculating brain of his as good a survival tool as any four-legged animal. But of course there are limits to Mr Fox’s power to discern other than what betokens his pure survival.

I am often struck as a devout animal lover of what actually goes on in the brains of animals, particularly in relation to our meeting with them. It’s the whole Thomas Nagal thing, “What is it like to be a bat?” His magnificent paper in the Philosophical Review of more than thirty years’ ago. The upshot to the paper is that Nagal believes that the nature of consciousness is widespread, while questioning subjective and objective experience. The bat at the centre of his thesis is notable because, Nagal argued, even if we could metamorphose into bats over time our brains would still not have been hard-wired from birth, hence we may experience the behaviour and habits of bats, echolocation and so forth, but certainly not the full conscious experience of being a bat.

Casting my gaze across the fields, indeed, other eyes fixed upon mine so my attention, easily swayed at the best of times, arced outwards as if searching for something lost and requesting help in my search and yet not. In a letter to Maria Gisborn, Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote:

I recall,

My thoughts, and bid you look upon the night.

As water does a sponge, so the moonlight

Fills the void, hollow, universal air.

What void, I always wonder? The line seems to perplex if not annoy me. The night sky and universe stretching into the unknowable beyond is far too much of a void to be filled by an object in relative terms no more than a spec of dust in our human eye. It could be I’m taking the poeticism of Shelly too literal or simply using it completely out of context and therefore fall foul of its true meaning. Probably that.

But one cannot help be transfixed by it nonetheless, the moon that is, especially on nights when its guise changes our perception, mainly into portent as it has always done down through the ages. This has to be the stark difference between man and other species; at the sight of such unquantifiable mystery no animal can grasp, in that self-reflective human manner, namely, existence and all it means as we try and fail to figure out our position in the universe.

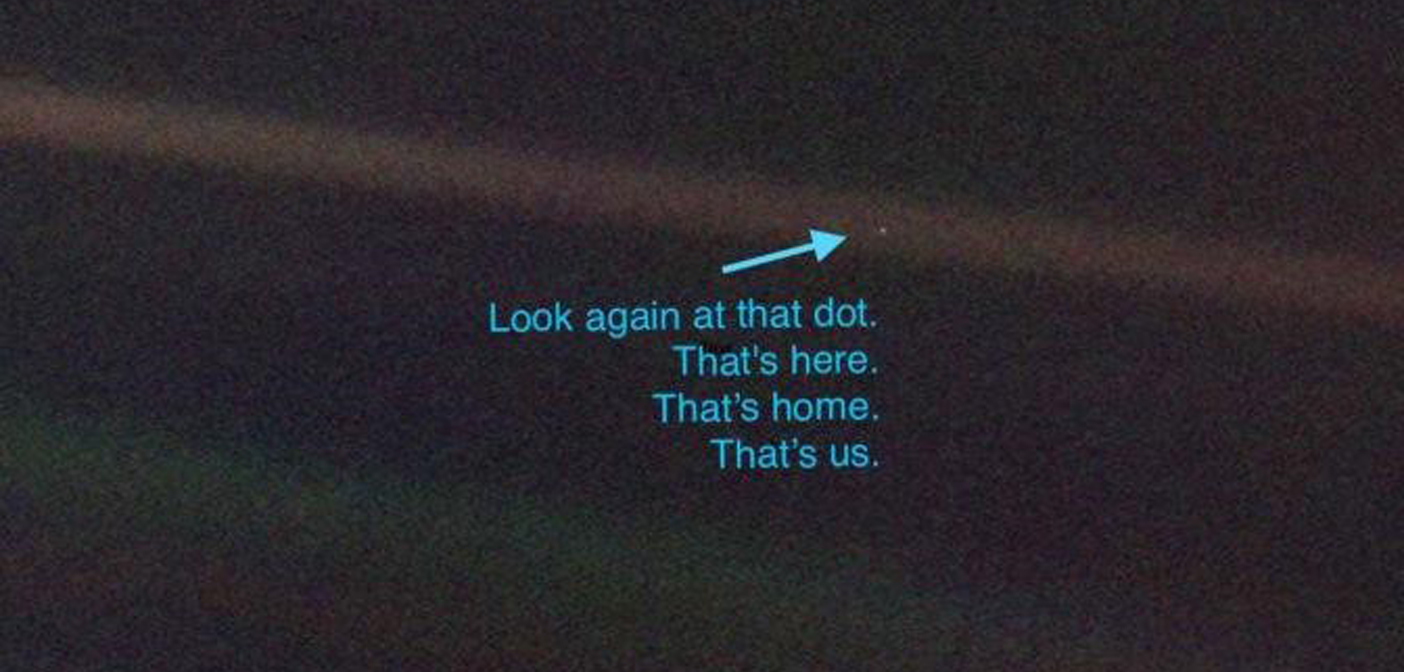

While living on the boat I was probably more attuned to the moon and Bysshe’s ‘universal air’. There wasn’t many nights that I did not wander outside, often in impenetrable darkness to see what show the night had put on for this single occupied seat in the theatre: me alone. Up beyond the locks in Llangynidr the bleach of street lights and car beams cannot penetrate and on more than one occasion walking home to the boat, my blind bearings nearly landed me in the canal (I never liked to use a torch). I had only ever experienced a similar kind of outside darkness when far north in the Sporades of Greece. The yacht I had chartered troubling us with a sputtering, and then quite dead engine so we had to tack into a small cove shortly before night fell, miles from any civilisation. My friend and I were astonished by what rotated over us that night; we had never seen a sky like it, billions upon billions of stars and planets and galaxies. Satellites speeded; the International Space Station; and shooting stars spilling out of every corner. The Milky Way too was clearly there, a brush stroke of sparkling grey, quite magnificent and awe-inspiring to consider our tiny existence within it, ‘the pale blue dot’ as Carl Sagan called earth seen from the Voyager spacecraft at a distance of 3.7 billion miles.

It was to be a few years later where that night sky in Greece was matched and perhaps exceeded. Closing in on the midnight hour I was travelling again with a friend over the Brecon Beacons, whereby we stopped the car just beyond the Storey Arms. There was no wind but the air was freezer-cold, a minty cleansing to the back of the throat with every inhalation. I have no doubt that we had lucked upon the precise conditions to allow us to see an incredible night sky. We must have stood there for half an hour, necks cricked, looking up and so aware that we were at that moment the first humans – yet wrongly of course – to be bowled over by the numinous sight. Following this thought, I wanted to get back in the car and rush home to take my dog out to share the experience.

I did, but he never looked up once as we climbed the mountain, merely followed every scent and then gave ineffectual chase to a fox that was already gone into its own universe of darkness.

I did, but he never looked up once as we climbed the mountain, merely followed every scent and then gave ineffectual chase to a fox that was already gone into its own universe of darkness.